STAAR Spark Reviews

The Language of Power: Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria (2018)

James Dobbyn, MSt Creative Writing

——————————–

Online since: 10 Apr 2019

Review process: Editorial Review

Suspiria. 2018. USA-Italy. Directed by Luca Guadagnino. Written by David Kajganich. Based on Suspiria (1977) by Dario Argento and Daria Nicolodi. 153 minutes.

Suspiria. 2018. USA-Italy. Directed by Luca Guadagnino. Written by David Kajganich. Based on Suspiria (1977) by Dario Argento and Daria Nicolodi. 153 minutes.

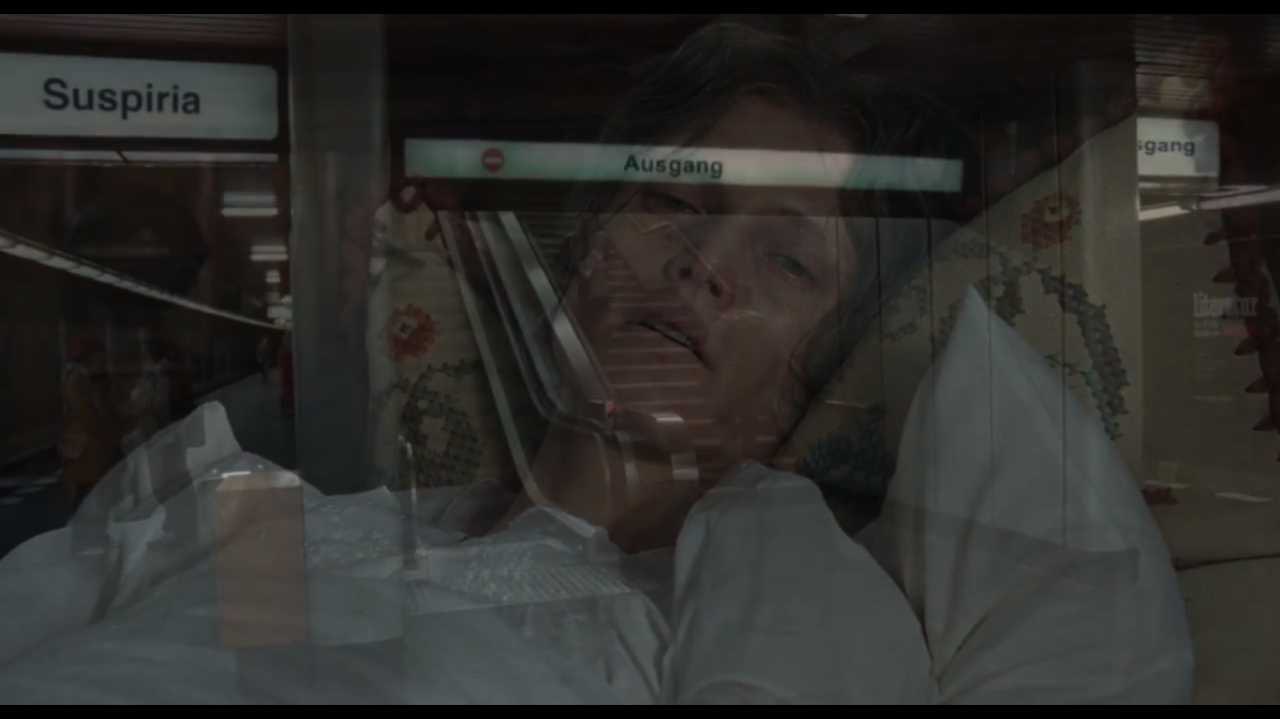

In the opening credits sequence of Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria, Thom Yorke’s haunting “Suspirium” is overlaid with the rasp of tortured breathing. The breathing belongs to the mother of Susie Bannion (Dakota Johnson), our main character. It hangs over the interior and exterior shots of Susie’s childhood home, omnipresent in the contained, rural setting. In the final shot of the sequence, the mother’s eyes stare lifelessly yet accusingly from her deathbed, straight into the camera. She dissolves into a shot of her daughter arriving in Berlin (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. (From Guadagnino, 2018).

Guadagnino’s Suspiria is a homage to Dario Argento’s 1977 film of the same name. The power of this opening sequence illustrates the meaning of its namesake: sighs. Sighs are the domain of Mater Suspiriorum, one of the three ‘Ladies of Sorrow’ of Thomas De Quincey’s Suspiria de Profundis (1845), from which Argento’s and Daria Nicolodi’s original screenplay drew inspiration. These are not sighs of boredom or longing but of total despair. They belong to ‘the baffled penitent reverting his eyes for ever upon a solitary grave, which to him seems the altar overthrown of some past and bloody sacrifice, on which altar no oblations can now be availing, whether towards pardon that he might implore, or towards reparation that he might attempt’ (De Quincey 1845). As we learn later, Susie’s birth is the irrevocable, unforgiveable sin for which her mother sighs: “She is what I smeared on the world”.

Violence and Fascism

Just as despair resides in the breath, so does power. In the maiming of the dancer Olga (Elena Fokina), one of the most effective and gruesome body-horror sequences in film, Susie’s controlled exhalations are intercut with her victim’s hyperventilations, whimpers, and screams of pain. Susie acts as a perverse puppeteer, breaking Olga’s body and throwing her across the room in time with the movements of her dance. And yet the force which injures Olga, who is isolated in a room deep within the Academy, appears to come from within her own body. This mode of ventroliquised violence represents a radical thematic departure from Argento’s Gothic conceptions of power and the body, which generate chills through psychological symbolisms.

In Argento’s Suspiria, threat most commonly appears in the form of a breaking-through or puncturing. See, for example, the hairy demon-arm which bursts through a window (Fig. 2) and seizes Patricia (Eva Axén), the way Patricia herself crashes through a glass ceiling at the end of a noose, or how one of those glass shards picturesquely embeds itself in her friend’s face. Likewise, Susie’s method of dispatching Markos is to stab her through the neck with what appears to be a large glass peacock quill (the symbolism of which is deliberately elusive).

Figure 2. (From Argento, 1977).

The Markos Academy’s oppressive aura is similarly figured in Argento’s version as a force pressing inward, crushing. In both versions, the protagonist’s body acts as the focal point of the coven’s collective power, but whereas Dakota Johnson’s Susie absorbs and channels it, Jessica Harper’s Suzy is weakened under its assault. The food, water, and blood-red wine she is forced to consume constitute an invasion of her body, which becomes the site of the coven’s control over her. In one scene, the black-clad, tyrannically German Ms. Tanner (Alida Valli) is seen literally forcing water down an ailing Suzy’s throat.

In Guadagnino’s retelling, this pressure bursts outward with violent energy. These are horrors of the soul, compulsions arising from deep within. In a scene in the witches’ communal living space, one (perhaps foreseeing the advent of Mother Suspiriorum) suddenly plunges a dinner knife into her own neck, killing herself. The thematic mirroring with Markos’ defeat in the original film dramatically highlights the interiority of this kind of violence. Both representations of control and force involve more-or-less overt references to German fascism but seem to disagree on the mechanisms of its operation. Argento’s model of fascism is hierarchical and downward-facing, originating with the ultimate evil (Markos) at its pyramidal apex. This model is optimistic about the individual’s ability to disrupt and destroy this hierarchy, to, as one character puts it, “cut off the snake’s head.” Guadagnino’s Suspiria depicts a bottom-up fascism which draws its power, like the ritual dance, from the decision of each dancer to remake herself ‘in the image of [the dance’s] creator,’ as Blanc says. It supposes the existence of an evil which cannot be destroyed and will only be reincarnated and reperformed, again and again. The most stunning narrative innovation in his retelling of Suspiria is the decision to root this evil within the heart of the protagonist. The primary source of narrative tension is thus shifted from a conflict between Susie and the witches to the conflict between the viewer’s idea of Susie and the reality of her character.

To the passive observer in a darkened audience, this form of narrative conflict is far more confrontational, almost accusatory. Because we are led to identify with Susie, her gradual transformation into Mother Suspiriorum becomes highly uncomfortable to watch. Olga’s mutilation is a pivotal moment in this transformation, a deliberate disruption of our mode of observation towards Susie, which up until this point has been that of aesthetic appreciation. Note that while Olga is alone within her mirrored prison, Susie’s dance occurs in the communal space as her fellow dancers look on.

The Political Dance

Depictions of the manipulated public sphere enacting forms of violent control are prominent throughout Suspiria. Contrary to the claims of reviewers such as the New York Times’ Manohla Dargis, Guadagnino’s use of the politics of the German Autumn is not merely a decorative set-dressing with ‘dead-end references both to 1970s German politics (cue the tear gas, riots and Baader-Meinhof mentions) and, more egregiously, to the Holocaust’ (Dargis 2018). Though the exploits of the Red Army Faction only ever seem to waft onto the screen like the smell of a bomb in the street, the two dramas are intimately linked. The violent unrest unfolding around the hermetically sealed Academy is reflected in the power struggle between two rival factions of witches: the first, led by the putrefying Helena Markos (Tilda Swinton), seeks a rebirth of the ailing coven leader’s power through a fresh vessel. The other, led by Madame Blanc (also Tilda Swinton), champions an aesthetic revolution which would surely spell destruction for Markos herself. Initially their conflict is mediated democratically, and Blanc’s support falls short of Markos’ power.

Just as the Red Army Faction (in its own view) strives to purge Germany of its Nazi elements and set it on a new political course, Blanc’s faction seeks a new apparatus of power, centered in the communal dance (Volk) and free of the rotting horror that is Markos. Ultimately, all it achieves is senseless bloodshed and a renewal of the cycle of violence. West Berlin itself becomes like Olga’s torture-chamber within the Academy, its inhabitants subjected to the force of the USSR’s projected power.1 In the same sense, this force is also channeled through the political body of the West German people as an insurgency. The existence of an end to this hideous dance seems highly dubious (indeed, the RAF’s campaign of terror did not end with the 1977 death of Andreas Baader). As Susie says to Blanc, “It’s all a mess: The one out there. The one in here. The one that’s coming”.

Dr. Josef Klemperer (again Tilda Swinton, as Lutz Ebersdorf) passes back and forth between these divided worlds in his role as “The Witness”. He ritualistically travels between his office in the West (his working, investigating life) and his dacha in the East (his ruminative world of memories). He alone can go from the regimented, regulated public space of police stations and quiet lunches into the insular world of the Academy, where even physical laws break down, and back again. He is the film’s lens on history and rationalism. A witness to the horrors of the Nazi regime, he sees ‘magic’ as a shorthand for the cult-like power of the group which denies the individual’s responsibility for its crimes (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. (From Guadagnino, 2018).

Guadagnino’s Suspiria is at its best when it is fully wrapped up in this dance of politics, history, and performance. It feels simultaneously urgent and visceral, in stark contrast to Argento’s dreamy, fairy-tale timelessness. By grounding the film as much in the body as in its German setting, Guadagnino produces one of contemporary film’s most gripping tales of the nature and exercise of power.

Power, Guilt, and Shame

The language of power, according to Blanc, is a nonverbal one. Guadagnino’s Three Mothers, like De Quincey’s Ladies of Sorrow, speak only in ‘pulses in secret rivers, heraldries painted on darkness, and hieroglyphics written on the tablets of the brain’ (De Quincey 1845). The dancer’s wordless movements shape the poems, prayers, and spells which are the essence of the witches’ power. Violence is the imperative and truest expression of this aesthetic power, and the body is both its conduit and its object – as Blanc says to Susie, “We must break the nose of everything that is beautiful”. And yet, there is nothing chaotic or indiscriminate about the dance or the violence – both rely on the structure of Blanc’s choreography to take form. Where they lack this form, as when Susie begins improvising during the performance of Volk, the spell is broken and the power-structure collapses.

The climactic purge of the Markosites (each of whom is pictured, literally up against the wall, in a cutaway immediately before her execution) is a ritual typical of all violent regime change. While the symbology and rhetoric of power change, its essence and exercise remain the same. Markos’ blasphemous propaganda effort, her self-stylization as Mother Markos and the ‘only mother,’ is a purely rhetorical claim to power. The true Mother Suspiriorum, a black, skeletal figure, remains totally silent as she delivers the kiss of death to Markos’ acolytes. As the ritual sacrifice prepared for Susie degenerates into a chaotic slaughter, it achieves its highest synthesis of the atavistic and the artistic. It is at this point that Susie appears most compassionate, cradling Sarah (Mia Goth) in her arms after granting her request for death. As the dancers wheel madly on the blood-soaked floor, Susie, now fully embodying Mother Suspiriorum, gasps, “Keep dancing. It’s beautiful. It’s beautiful”.

While Argento’s Suspiria ends on a shot of the Academy in flames, the coven destroyed forever, Guadagnino envisions its continuation under new leadership. The result is a far more unnerving conclusion – the look on Miss Tanner’s (Angela Winkler) trembling, blood-smeared face as she surveys the remainder of the Academy’s students could be a vacant, shell-shocked stare or terrified anticipation of what is to come (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. (From Guadagnino, 2018).

The absolution which Susie/Suspiriorum delivers to Dr. Klemperer by wiping his memory is also unsettlingly ambiguous. “We need guilt and shame,” she insists, “But not yours.” This reassurance seems disingenuous in light of the film’s insistence on the deep-rooted nature of evil and the dangers of unconsidered participation. The most important word here is “we”. Is Susie speaking on behalf of a modern world which wishes to exorcise the demons of the past, or is her “we” aligned with those very demons? Johnson’s simultaneously soothing and menacing performance betrays nothing. As the horrors of the mid-20th century begin to die out of living memory and far-right nationalism sees a surge across the developed world, a shared anxiety is born: Is it all right to forget? And when we have forgotten, what comes next?

1It is worth noting here that the USSR is thought to have been provided with training, weapons, and logistical support by the East German Stasi, whose ‘agents trained Red Army Faction members to use the anti-tank grenades they fired in a failed attempt to kill Gen. Frederick Kroesen, commander of American forces in Europe, in September 1981’ (Kinzer 1991).

Filmography

Argento, D. 1977. Suspiria. [DVD]. Film Four, 2008.

Guadagnino, L. 2018. Suspiria. [DVD]. Lionsgate Home Entertainment, 2018.

Bibliography

De Quincey, Thomas. Suspiria de Profundis. William Heinemann, 1861. Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/23788/23788-h/23788-h.htm.

Dargis, Manohla. “In ‘70s Germany, A Gory Freakout of Female Power.” The New York Times, 26 Oct. 2018, p. C8. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/24/movies/suspiria-review.html.

Kinzer, Stephen. “Spy Charges Widen in Germany’s East.” The New York Times, 28 Mar. 1991, p. A00011. https://www.nytimes.com/1991/03/28/world/spy-charges-widen-in-germany-s-east.html.

The Language of Power: Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria (2018) by James Dobbyn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

<< Back to Spark Reviews

<< Back to Publications

St Anne's Academic Review (STAAR) A Publication by St Anne's College Middle Common Room ISSN 2048-2566 (Online) ISSN 2515-6527 (Print)