STAAR Spark Reviews

From Barbecues to By-elections: Feeling through the Future in Russell T. Davies’ Years and Years

Michael Bicarregui, MSt. in Film Aesthetics

——————————–

Online since: 30 Aug 2019

Review process: Editorial Review

Years and Years. 2019. UK. Written by Russell T. Davies, directed by Simon Cellan Jones (4 episodes) and Lisa Mulcahy (2 episodes).

Years and Years. 2019. UK. Written by Russell T. Davies, directed by Simon Cellan Jones (4 episodes) and Lisa Mulcahy (2 episodes).

Danny Lyons, a council worker who manages temporary housing for asylum seekers, offers his neighbour a lift while driving past her on their Manchester street. Fran tells an initially-bemused Danny that she is a professional storyteller; later in the episode, Danny has arranged for Fran to bring her act, the tale of a woman who circumnavigates the mouths of hungry animals by hiding inside an enormous pumpkin, to the refugee camp where he works. Amongst an enraptured audience, Danny listens to Fran’s story with Viktor, a Ukrainian refugee who will soon become his lover. This scene of narrated wonder ends with a cut to a starker shot of both characters standing behind wire fencing (Fig. 1). A sharp contrast, this cut juxtaposes the freedom of narrative immersion with the real-world politics that confine and cage individuals. In this encounter, storytelling rests as a precarious form of empowerment, transporting Viktor to a fantastical world of free movement, but drawing poignant attention to the borders imposed on him. Through this metanarrative device, Russell T. Davies sets up Years and Years as a six-episode whirlpool of thickening plot, political confusion and family conflict, where story, including the story Davies is writing, acts as an alternating current between truth-telling and manipulation, escapism and cold reality, the weightless virtual realm and grounded geographical stakes.

Figure 1. (From Davies, 2019)

Fran proffers to Danny that stories let us ‘make sense of the world’. Meanwhile, the series opens with the related words ‘I just don’t understand the world anymore.’ This statement is made by Vivienne Rook, Davies’ analogue for the Trump-Farage figure. Rook’s project, like those of her real-world iterations, is to complain that the world is increasingly convoluted while ensuring that no one can understand her own network of political actions and statements. Rooke’s image surrounds the series’ principal characters, the four siblings of the Lyons family, looming on billboards, televisions, laptops, and phone screens, shifting intangibly between the background and foreground of each episode’s shots, and the characters’ minds. If stories enable us to process and understand reality, Rook is the politician who weaves overwhelming and self-contradictory rhetoric to escape narrative’s grasp. An undecodable figurehead, Rook becomes the epicentre of an interplay between dichotomies of sense and senselessness, economic connection and cultural discord, meaningful narratives and untraceably modulating soundbites. Through this conflict between story and the struggle to form it, Years and Years plots a trajectory of Britain in the worryingly near future, yet Davies’ real triumph is a move beyond mechanism to humanity, illuminating the personal side of political and technological change.

‘It’s just like Viv Rook says’: Languages of Politics and Elitism

Davies interrogates the precise mechanisms by which far-right politics burrow their way incrementally into acceptable public discourse: in a series of brash generalisations crammed with subtle nuances, the parasitic Rook misleads and redirects the political conversation, using her peripheral position to avoid accountability. In her first appearance, Rook is almost excluded from a televised panel for claiming not to ‘give a fuck’ about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The episode traces various characters’ responses to this comment, ranging from ‘she can’t say that’ to ‘she’s brilliant’. Years later, Rook flickers chillingly between humorous references to her ‘little faux pas’ and sincere proclamations of her victory against ‘censorship’. Yet even in that initial scene, Rook easily evades the censors by switching the word ‘fuck’ to ‘monkeys’. By changing one word, Rook casts herself as a hero of free speech instead of an apathetic monster, branding those who attempt to preserve respect and compassion as an out-of-touch elite. Rook’s speeches stir up political frustration akin to the sensation one feels in a nightmare, where situations unfold and the dreamer has no power to prevent them.

Davies also elucidates the link between rises in anti-academic sentiment and the normalisation of far-right politics. After months of Rook’s media bombardment, Rosie Lyons criticises an elite of ‘the bankers, the experts’. Echoing Michael Gove’s infamous statement that people have ‘had enough of experts’ (2016), this conflation demonstrates how blame for the disenfranchisement of ordinary people is directed away from true causes of inequality towards projects of knowledge and understanding. This media-engineered distrust of all things intellectual dilutes public awareness of how injustice is perpetuated and deprioritises fact-checking in political discourse. For example, Ralph is frustrated by Danny’s scepticism towards a website claiming the non-existence of germs. Gradually, the culture shifts: respectful debate is demonised as censorship and critical thinking is rebranded as an ivory tower; Rook spreads political lies while also brandishing the universally-applicable accusation of ‘fake news’.

Davies turns the convolution of society into a case for understanding and compassion, distinguishing between the intellectual and the elitist by demonstrating the difference in his own intricate writing. Mastering its well-informed and self-reflexive intelligence, Davies’ script remains rooted in a process of validating and empathising with the experiences of ordinary people. Precisely by understanding the characters, their emotions, how they speak and absorb political speech, Davies demonstrates exactly how Rook lacks this empathy. Davies’ answer to concerns of academic elitism is to make nuance and critical thought understandable.

‘Hotter and faster and madder’: Technology, Pace, and the Personal

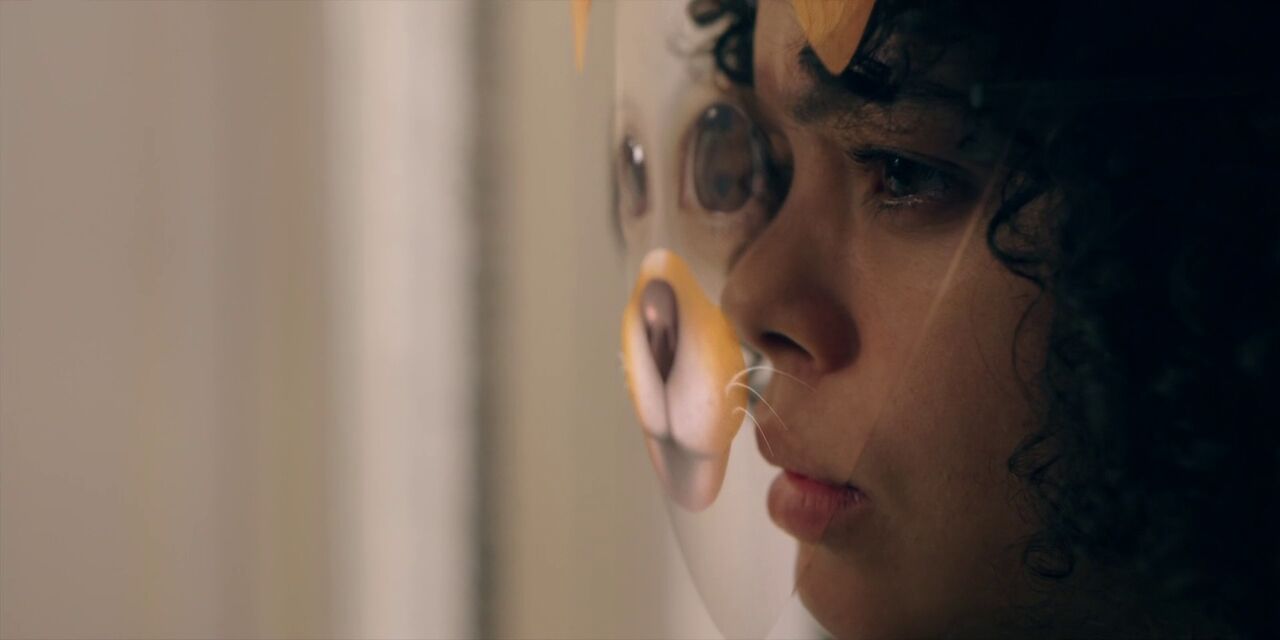

Just as Years and Years splits the atom that conflates elitism with thought, so does it sift apart technological innovation and the dangers of a virtualised world, separating technophobia from healthy scepticism. The first episode opens with warm, connected family relationships facilitated by smartphones, which evolve into the ‘family link’ through which the four siblings regularly communicate. Rosie organises a date by tapping phones with a prospective partner for his address, but is alienated on discovering his sexual activities with a humanoid robot named Keith. An ordinary family breakfast is broken by eerie conversation mediated by a real-life ‘filter’; one sinister shot has the camera track around Stephen Lyons’ daughter Bethany’s head, revealing her distressed face hidden behind the superimposed cartoon mask that simultaneously protects and isolates her (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. (From Davies, 2019)

Edith Lyons, an overseas activist, asserts in an interview that ‘the world keeps getting hotter and faster and madder’, and the pacing of Years and Years communicates this speed, adapting its visual grammar to the racing technological world it documents. When the Lyons siblings communicate using the family link, which is hosted by an Alexa-style device in each of their homes called ‘Signor’, the scene cuts between shots of the characters speaking and listening to each other as if they were engaged in a normal conversation in the same room, the camera passing through the link with seamless connectivity. Yet each cut displays a different household’s background, a different side conversation running amongst each sibling’s immediate family. This frequent cutting between multiple sets of surroundings accommodates for a script whose information flow is rapid and complex, lending these domestic scenes an engaging pace while enabling the siblings’ characters to be quickly developed by comparison with each other.

Davies also writes rapid pace into the series’ wider narrative structure. Each episode, set a year after the last, features a sequence that cuts between the explosive motif of New Year fireworks, televised news clips, and substantial developments in the life of the Lyons family. These sequences, with a punchy score, compress a year of current and personal affairs into minute-long reels, linking the characters’ lives to broad socio-political tides. Alluding to social-media-style videos made up of a few seconds of footage from each day in a year, these highlights reels tap into how we feel and measure the sensation of time’s passage in the modern world of media saturation.

Figure 3. (From Davies, 2019)

As well as offering a critical response to technology while showing its benefits, Years and Years offsets the tone of the family link and newsreels with scenes set in the siblings’ grandmother Muriel’s spacious but decaying house (Fig. 3). Muriel and her world, in which ‘the tsunami is an entirely modern invention’, act as a ballast that prevents the series from losing the feeling of weight as it soars into a future of hopes and terrors. However, rather than positioning the grandmother as a stock luddite, Davies uses Muriel’s character to personalise and ground the story’s futuristic elements. By the last episode, Muriel asks her great-grandchild to retrieve the ‘old Signor device’, now obsolete, from the back of a kitchen cupboard, explaining ‘I like having something to look at’. When Signor lights up to explain Muriel’s reference to Shirley Valentine, ‘lost on’ her family, she delightedly exclaims ‘You see? My little friend’ (Fig 4). Anne Reid’s performance, absorbing technological change into a refreshing and comforting mundanity, communicates and makes believable the charming nostalgia Muriel holds for this electronic device of a future past, an emotional attachment to a cultural relic that the Lyons siblings cannot understand.

Figure 4. (From Davies, 2019)

Where Muriel is not offsetting the future’s pace with her old ways of gardening and fussing over her great-grandchildren, she lends Davies’ technological predictions a sense of real history by absorbing them into lived experience and oral, almost-ancestral memory. Muriel’s resurrection of Signor offers the possibility of resistance through memory, holding onto the outmoded in the face of a society that prefers to forget the past. Eventually, Edith hopes that downloading human memories onto molecules of water will permanently record, archive and validate personal histories, addressing problems of data preservation in the digital age and defying regimes that erase their own oppressive acts.

Davies also complicates the series’ futuristic style through interactions with carnivalesque imagery. Along with each episode’s firework displays, multiple scenes depict characters dancing and rioting around fires; one disorderly yet almost-ritualistic family brouhaha is tied into distinctly modern experience by its pop song soundtrack (Fig. 5). Davies’ consistent return to the carnivalesque blends his vision of the future with historic methods of aestheticizing public consciousness, celebration and oppression, and the passage of seasonal time. Despite their misfortunes, the Lyons family continue to gather for an annual ‘winter feast’; this determination to celebrate in the face of adversity reasserts the characters’ relentless humanity, while also highlighting their complicity, escaping into temporary exhilaration and failing to object to the social changes taking place around them. As the simulated chaos under Rook’s rhetorical spell disguises an authoritarian regime, Davies adopts carnivalesque images and narratives to approach and understand the frenzied madness of this dystopian story.

Figure 5. (From Davies, 2019)

‘It’s all your fault’: Compassion in the Virtual World

Through examinations of how technology integrates into lived experience, Davies sets British television’s social realism in dialogue with aesthetics and ideas from post-humanism and science-fiction. While Bethany’s computer-chip implants enable her to feel the sensation of being anywhere in the world, Rook uses the ‘blink’, which disables nearby online devices, to block the transfer of information out of concentration camps. The blink is a virtual tool that creates pockets of real geographical isolation, merging the physical and simulacral realms into a dystopian but grounded space. While the Lyons family communicate virtually across borders of counties and nations, the filmmaking style homes in on challenges of actual transit, prioritising images of cars, vans and boats, gates, cages and barriers (Fig. 6). Davies pays constant attention to his characters’ lines of movement, defying the nebulous array of constantly shifting and untraceable connections that mirror Rook’s political rhetoric.

Figure 6. (From Davies, 2019)

Much of the human drama in Years and Years revolves around decision-making in the virtual domain. Ralph, furious at Danny’s affair with Viktor, uses his phone to photograph and report Viktor while he works illegally in a petrol station, another liminal space of unsustainable explosivity. The camera shows how virtualised detachment prevents and protects Ralph from realising the human impact of his actions. Ralph turns away from a close-up on his conflicted face, leaving a wide shot of Viktor out of focus behind a window. Ralph turns again, lifting his phone into the foreground of the same shot and we see Viktor in profile through the phone’s screen, now in a tighter frame and clear focus (Fig. 7). The real view of Viktor, safe and anonymous, is surpassed by a digital image that exposes and threatens him. When Viktor comes into focus through the phone screen, so does Ralph’s resolve, in a shift from moral uncertainty to vengeful clarity. Viktor’s life is reduced to a collection of movable pixels that enables others to manipulate him with reduced emotional consequences in their own lives. However, along with Muriel’s attachment to Signor, Bethany’s disquieting smile while contemplating full bodily integration with the digital, and her horror as she watches the passing of another computerised sentence for Viktor, display more compassionate and embodied understandings of the virtualised world.

Figure 7. (From Davies, 2019)

‘We don’t have to look that woman in the eye, the woman who’s paid less than us’: Current Affairs and Conclusions

Technology, therefore, becomes a vital part of the characters’ moral lives, and Davies writes their decisions and personal stakes in startlingly convincing integration with infrastructural change. The resonance in this writing of the future relies on its grounding in the non-fictional present. Stephen’s extreme exploitation as a courier, or ‘lifestyle enhancer’, is only a minor exaggeration of the working conditions and contracts of Uber and Deliveroo drivers. His manager’s claim that ‘you make people’s life feel better’ connotes the present economy where we are encouraged to take advantage of increasingly demanding services and ignore the livelihoods of the people who provide them. Rook appears on television promoting ‘British wine for British people’, alluding to Tim Martin’s anti-EU campaign removing European products from Wetherspoons pubs. Viktor’s struggle in border crossing is hardly changed from today’s reality, from the UK’s ‘hostile environment’ immigration policy to Italy’s ban on rescue boats docking in its harbours, leaving refugees to drown in the Mediterranean Sea.

Davies is unafraid to face the complicity we all share in harmful systems, expressing it deeply and widely, from Muriel’s rant about the disappearance of supermarket till workers due to automated checkout machines, to Rosie’s voting for the woman who oversees the deportation of her brother’s partner, political actions that produce psychopathy through complacency and unawareness. Listening to her grandmother connect her decisions with wider cultural shifts, it is Rosie’s realisation of her power to impact the system, positively or negatively, that inspires her to fight back. Davies refuses to shy away from positioning one moral act as human brilliance, and another, no matter how understandable, as human failure.

However, these bleak aspects of Years and Years are, in some senses, reassuring. Fran emphasises to Danny ‘the shape of stories, and the need for them’; we do not just require narratives to understand the world, but narratives with shape, quality, and affect. It is inspiring to know that there are writers, in positions of privilege to write, who both understand the need to address the current state of politics, culture and technology, and have the talent to encompass vast cultural mechanics and compelling intimacy with human emotion and behaviour. Far from depressing, Years and Years proves that television remains a force for engagement, integrity, and honest commentary. Davies captures the sensation of today’s current affairs: the feeling that we have no idea what is going to happen. Lucy Mangan (2019) observes the ‘sense’ of the characters’ ‘inner gimbals ceaselessly recalibrating, like ours’, to each political development. Through the most baffling and distressing events, Davies tunes into human experience with curiosity, insight, and empathy: as the rightly terrified Rosie asks in the final moments of episode one, ‘what happens now?’.

Filmography

Davies, Russell T., 2019, Years and Years, Episodes 1-6, BBC, accessed online via BBC iPlayer.

Bibliography

Mance, Henry, 2016, ‘Britain has had enough of experts, says Gove’, Financial Times, 3rd June 2016.

https://www.ft.com/content/3be49734-29cb-11e6-83e4-abc22d5d108c.

Mangan, Lucy, 2019, ‘Years and Years review – a glorious near-future drama from Russell T. Davies’, The Guardian, 14th May 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/may/14/years-and-years-review-a-glorious-near-future-drama-from-russell-t-davies.

Squires, Nick, ‘Italy to fine migrant rescue boats up to €1 million as tough Salvini law passes’, The Daily Telegraph, 6th August 2019. https://www.euronews.com/2019/07/30/eu-seeks-volunteer-countries-to-take-in-migrants-stranded-at-italian-port

‘Wetherspoon to stop selling champagne and prosecco’, BBC News, 13th June 2018. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-44465657.

From Barbecues to By-elections: Feeling through the Future in Russell T. Davies’ Years and Years by Michael Bicarregui is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

<< Back to Spark Reviews

<< Back to Publications

St Anne's Academic Review (STAAR) A Publication by St Anne's College Middle Common Room ISSN 2048-2566 (Online) ISSN 2515-6527 (Print)